What Inspired the Writing of Bloodlines

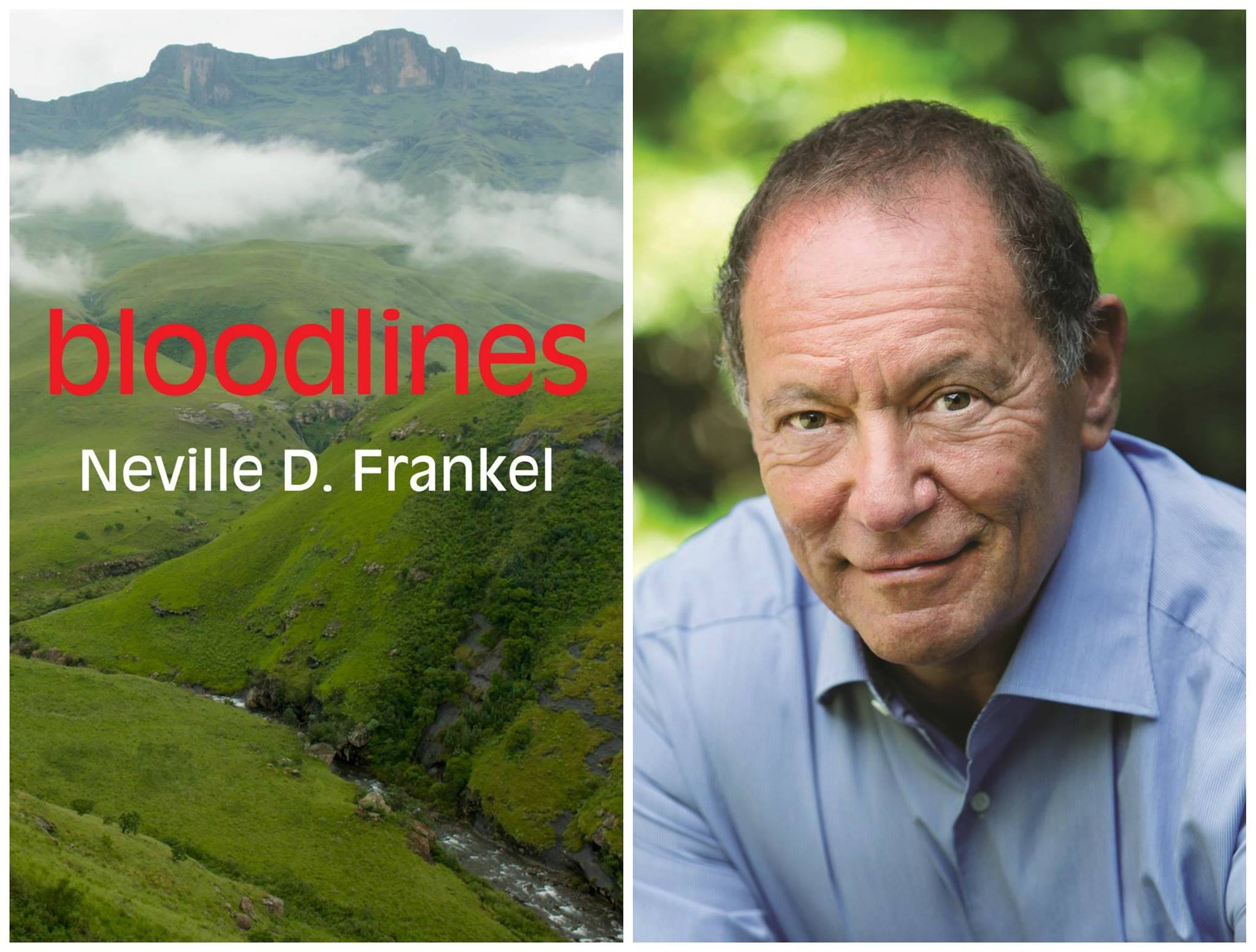

We left South Africa in 1962, when I was 14, just after Nelson Mandela was imprisoned. A year before we left, there were anti-apartheid demonstrations at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg, and many of the student leaders had Jewish names. Fifty years later, I can still hear then Prime Minister Verwoerd’s voice, speaking English on the radio in his deep, guttural voice. “Jewish parents,” he warned, “keep your children at home.”

When we first arrived in Boston, I was a teenager whose only goal was to become an American; I had no interest in the country I came from. It wasn’t until I reached my forties that I became interested in South African history, and what was going on at the time we left. What I discovered opened my eyes to possibilities that I had never imagined.

In the early sixties, middle-class South Africans were placing their lives, their liberty, their future and the futures of their children, at risk by working for anti-apartheid organizations banned by the government. They demonstrated, picketed, transported striking workers, hid and ferried activists sought by the police out of the country. Many of these activists were liberal Jews descended from the Eastern European refugees who made their way to South Africa in the first half of the century, often bringing with them a history of socialist or communist activism. It was perhaps their—or their parents’– political sensibilities that drove them to take such risks, and many suffered imprisonment, beatings, and even death at the hands of the police and the Special Branch.

I had the same family history as the activists who took such risks; my maternal grandparents came from Eastern Europe, and my social-activist paternal grandfather left Germany in 1913 as a boy and was interned in South Africa by the British in World War I (he may have been a Jew, but in the eyes of the British he was first a German). The ironies of history!

In 2002, forty years after leaving, and at the behest of my wife and children, I returned to South Africa for the first time. I saw the changes that had taken place since Nelson Mandela was elected and apartheid came to an end, and I discovered in myself a surprising interest—and perhaps even a longing—for the past I might have had. I began to wonder what my life might have been like if, instead of leaving the country, my family had been committed to the overthrow of apartheid? During that visit, the story of Bloodlines began to take shape.

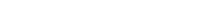

Bloodlines became the story of Steven, a young boy who leaves South Africa with his father, Lenny, in the early 1960s after his mother disappears from their lives. They end up in Boston, where Steven grows up believing that his mother was a hero who died fighting apartheid. Not until he is in his forties with young children of his own, and his father Lenny is on his deathbed, does the story begins to unravel, and he realizes that the family history he has treasured is a fabric of half-truths and lies.

The novel is about Steven’s discovery, told by his father, his mother, and her lover, of what actually happened in the years between the early sixties and the present. It is a novel of political intrigue and violence; of families broken up and lives destroyed by events more powerful than any individual; of family secrets and the impact they have on parents and children over decades. It is about the way an immigrant Jewish family’s political and social beliefs become strained as they transfer to the next generation; about the similarities between traditional Jewish ritual and values, and the practices of the Zulu people living in isolation in rural Zululand, now called Kwa-Zula Natal. It is also a story of love and sacrifice–a father’s love; the sacrifices a man makes to protect even an unfaithful wife; a mother’s love for her son, kept a secret for forty years; the painful love of two people who insist upon a life together even though their union is prohibited by law. Finally, it is about the possibility of reconciliation, and the recognition that even if one is fortunate enough to find it, it seldom takes the form one expects.