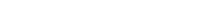

Gifts from My Father

Life’s gifts have a way of materializing in unexpected forms. It is up to us to recognize and grab hold of each gift before it evaporates into thin air.

Last week my 92-year-old father fell and broke his hip. He was hospitalized and received a hip replacement — not an easy experience for anyone, let alone a man in his nineties.

Nevertheless, it was a gift. We are fortunate to live in the United States, where such advanced treatment is available, where there is no cutoff based on age or financial means, and where surgery could be performed just one day after the trauma took place.

The second gift: My father has been an inveterate swimmer and a careful eater all his adult life. In the early years, when he refused cream and insisted on yogurt before the rest of the country knew what it was, we all laughed at him. Thank goodness he did. Because he — and my mother — so diligently maintained their health, he was strong enough to withstand the assault of major surgery in his tenth decade.

But it hasn’t been easy. Following surgery and the accompanying general anesthesia, my father had periods of confusion. At times, he insisted on getting out of bed to walk around, unable to remember that he was too frail to stand, and that even if he could, walking was impossible. We decided that it was unwise to leave him alone, and arranged to have a family member with him at all times, even spending the night at his bedside in the hospital. That way, if he woke and tried to get up, he would at least have a familiar face in the room beside him.

The third gift was evanescent and transitory; we could easily have missed it, written it off as an annoyance or an obligation. Some might have resented the prospect of spending time with a confused old man. But this man was also our father.

Instead, we embraced it, and him. All his life, he has been a loving, considerate, and measured man, dispensing advice, counsel and humor to generations of his own family — family by blood and what he calls ‘family by choice’ — with ease and humility. As a physician, he helped train generations of physicians, some of them now close to retirement themselves. He gives of himself easily, has always been interested in the lives of others.

Because of who he has been to us, and the kind of man he is, we welcomed this opportunity to spend time with him. For some, it was a way to give back to him. For others, it was a chance to spend time with a beloved father and grandfather. For all of us, it was an expression of love.

In caring for him, we also gave ourselves an unexpected and extraordinary gift. Some people — among them medical practitioners of all stripes, nurses, doctors, caregivers, saints — know instinctively that the rewards of caring for others can be immeasurable. But, for most of us, this knowledge comes as a revelation.

♦◊♦

It turned out to be easy to be patient and loving with him in his vulnerable and confused state. And, it turned out, at least in my father’s case, that his confusion was interspersed with moments of fierce lucidity. Knowing him, I shouldn’t have been surprised. His natural state for most of his life has been one of fierce lucidity.

The nurses who tended him were not angels. That’s far too tame and easy a description. They were flawed, sometimes weary human beings; highly trained and completely competent in their discipline; brimming with kindness and compassion.

Unable to stand on his own, my father had one lengthy episode after another in which he had to be helped to use the bathroom. After each experience, he lay on his hospital bed, glassy-eyed with exhaustion. When I asked him how he was doing, he looked at me with amazement.

“Do you think there’s an adequate way,” he asked hoarsely, “to thank these extraordinary people for taking care of me with such grace and tenderness?”

And so it was, even in his confusion, that the humanity that has been a hallmark of his life shone through.

♦◊♦

In the quiet hours following midnight, we sat together in his hospital room, talking about the past. His past, and mine. His parents’ history. Memories of his own childhood in South Africa, some of them tearful. His father, talking about him to a stranger when he was eight years old, and saying in Yiddish, “I have only one son. But he’s a good one.” From my grandfather, this must have been high praise indeed, able to elicit tears after almost nine decades.

“What a foolish old man I am,” he said, “to be concerned about such childish memories in my nineties.”

My father and I are devoted to each other; we share a mutual respect that couldn’t be deeper. At this stage of our lives, our love for each other is completely lacking in ambivalence. But it wasn’t always that way. The only son of immigrants from Europe, my father felt that he was the repository of all his parents’ ambitions and dreams, a burden that made him a serious and studious child. Stresses in one generation have an impact on those that follow, and we were no exception. As father and son, he and I struggled as I was growing up. He couldn’t understand, he said in the hushed intimacy of the still hours preceding dawn, why I, his elder son, hadn’t automatically shared his values and goals. As a result, he said, as a very young parent he had perhaps been harsher on me than he ever intended or realized. I think the confession was a gift that lifted a great weight of guilt from his shoulders.

It was also a gift of monumental proportion to me. At last, I can accept that if there was conflict between us in my early years, there was enough blame to go around. Neither of us was perfect. What a relief to know, finally, that as I boy I didn’t really do anything to disappoint my father.

What a foolish old man I’m becoming, I thought, to be concerned with such childish memories. Why, I wondered, as I approach seventy, should they still be important to me?

For the same reason that my father weeps at the memory of his own father’s muted praise. Because we never really leave our childhood behind. Because even when childhood conflicts are resolved, they remain like irritants in the shell of the oyster, pearls in the making.

Perhaps, because fathers and sons, mother and daughters, parents and children, are really the same person in different skins, living through and resolving similar issues in different ways. Perhaps because generations are all the same, distinguished only by the order in which we come into being, and then evanesce.

My father is recovering now, slowly. I have read this to him and received his open-hearted permission to share it.

Thanks, Dad, for everything.